The Iroquois called it Ohi:yó meaning “Good River.” The French called it “La Belle Riviere.” It has become something considerably less and much more.

The Ohio River begins at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers in Pittsburgh and ends as it joins the Mississippi near Cairo, Illinois. The 981-mile river flows through or along the border of six states, and its drainage basin includes parts of 14 states. Running east-west through much of its length, it knits together the cultures of Appalachia, the East, South and Midwest.

The Mississippi is longer and more famous, but it can be argued that the Ohio has been equally important in the history, development, economy and politics of America. In that way, it is most reminiscent of the great rivers of Europe, like the Danube. And it can be spectacularly beautiful. Or not.

The river has great significance in the history of the Native Americans, as numerous civilizations formed along its valley. For thousands of years, they used the river as a major transportation and trading route. In 1669, a French expedition became the first Europeans to see it. The river then served as a border between present-day Kentucky and Indian Territories. It was a primary transportation route for pioneers during the westward expansion of the early U.S. During the 19th century, the river formed part of the border between free and slave territory, Where the river was narrow, it was the way to freedom for thousands of slaves escaping to the North, many helped by free blacks and whites of the Underground Railroad resistance movement.

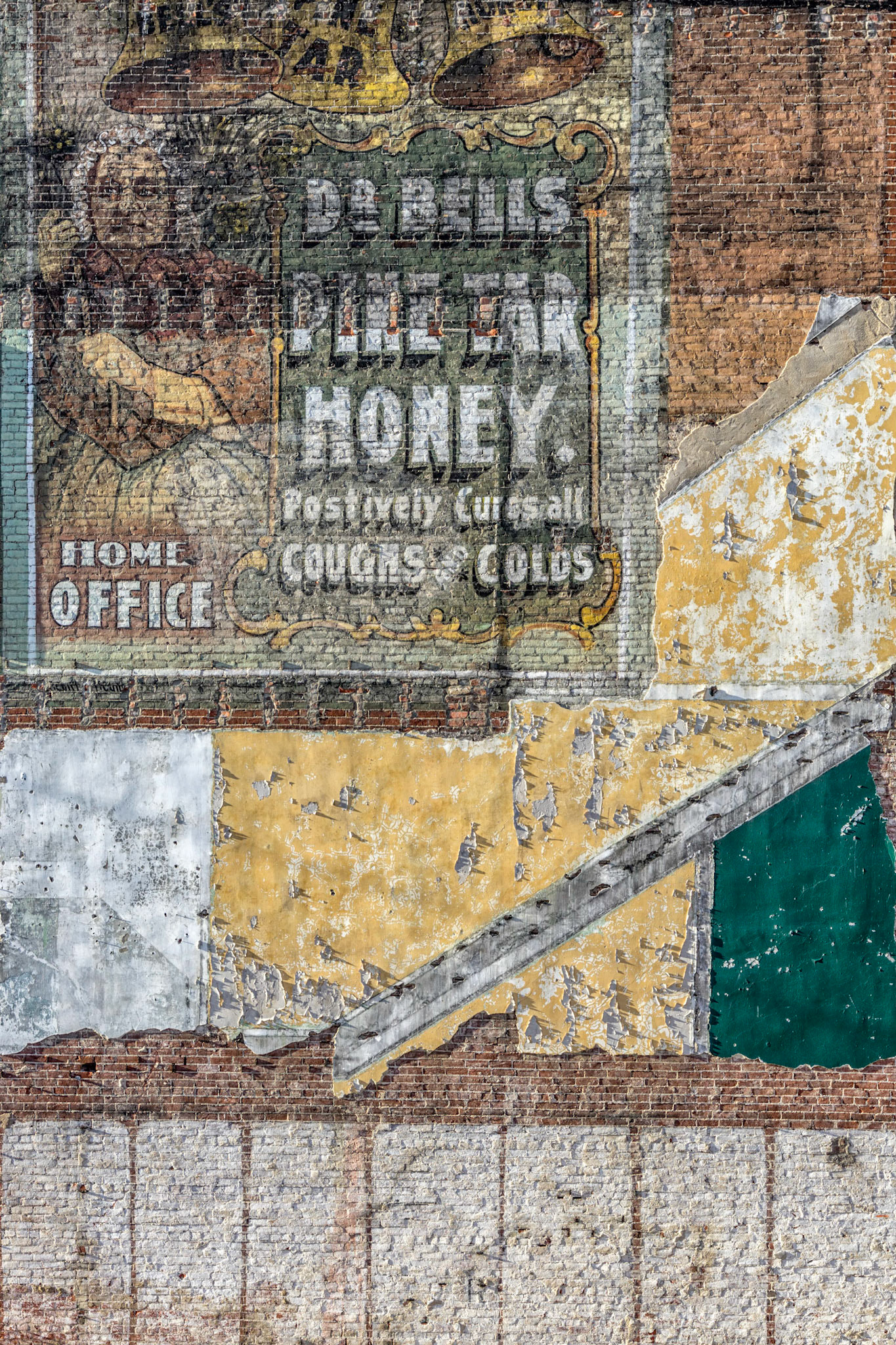

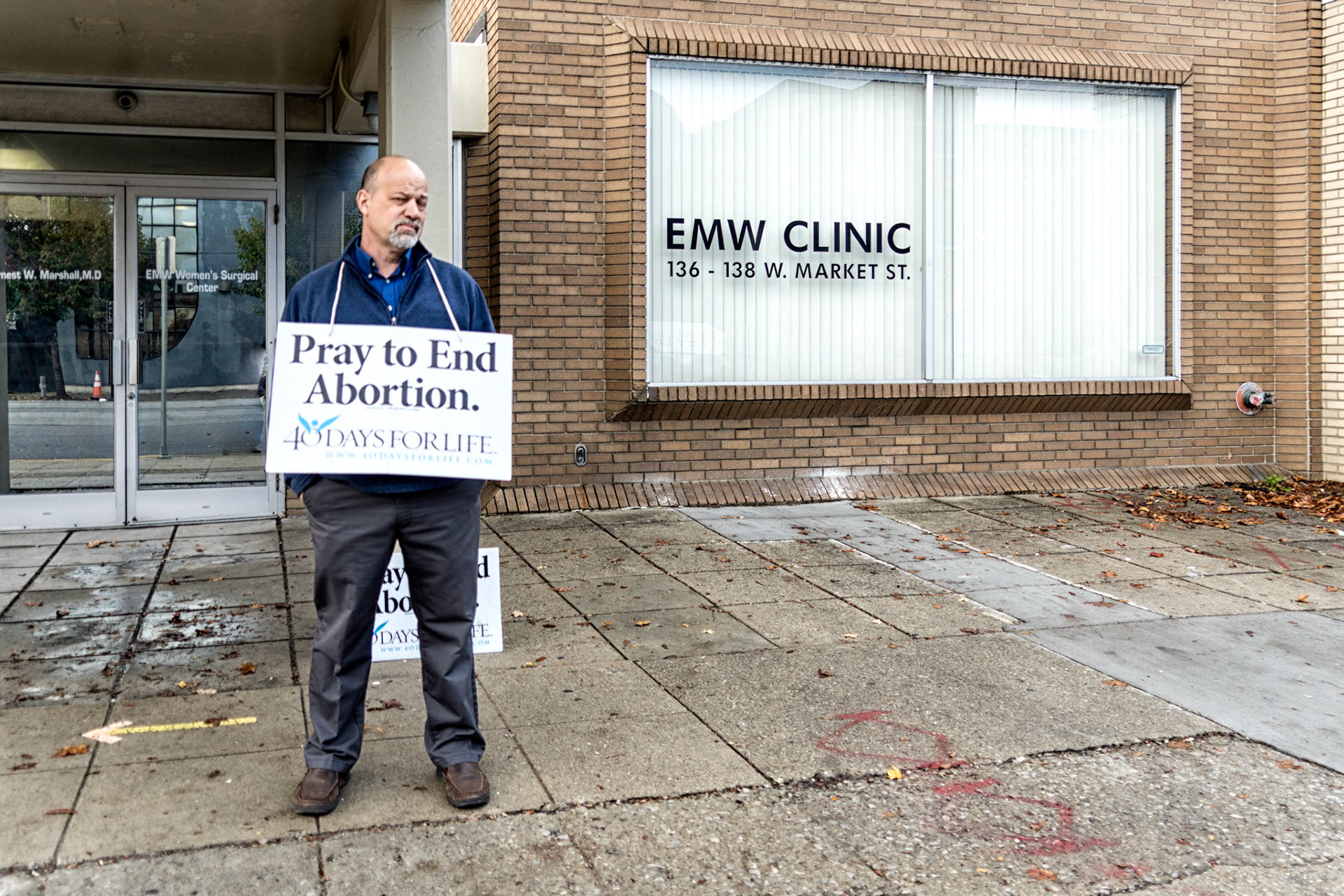

In 1785, Thomas Jefferson stated: “The Ohio is the most beautiful river on earth. Its current gentle, waters clear, and bosom smooth and unbroken by rocks and rapids, a single instance only excepted.” But the Industrial Revolution’s legacy was a dirty, polluted, dammed and locked perversion of a river, especially closer to Pittsburgh. As one drives the roads parallel to its banks, there is hardly a moment when there is not a giant power plant (or the billowing smoke therefrom) visible either through the front or rear windshield. Due to efforts of citizens and government over the past 50 years, the river is considerably cleaner today. But that is not the only reason. Many of the factories, warehouses and mines that employed hundreds of thousands are memories; the river cleaner simply from their absence. And many of the places those people lived in are close to ghost towns, hollowed out and pale versions of better times. Many of the storefronts are used for almost anything else than new merchandise: bric-a-brac, recycled antiques, local crafts, real estate listings. The residents remaining are overwhelmingly white, religious, conservative, proud and fiercely patriotic; pristine American flags hanging even from buildings that seem abandoned. This is the story that played out in our recent Election.

However, these towns are small architectural treasures, the main streets and Victorian homes waiting patiently for a renaissance that may never come as the country and economy have changed, seemingly without a thought for places like this. It seemed to me that for those that remain the rewards of small town life were more important to them than the economic challenges ahead of them.

The bigger cities -- Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and Louisville are thriving, diverse and looking forward. Some of the small towns that have colleges or operational industry are doing well. A tiny few have become tourist attractions based on the perfection of downtowns next to the river. But for many others, not so much. The effect is one of bending time; as the river lazily turns on itself, you come upon the future of one city or town and the past of another.

All images captured within 1/2 mile of the river. I traveled more than 3200 miles by car, foot and boat to explore every town, access point and all 55 bridges to see the river from as many angles as possible.

Pittsburgh

Cincinnati OH

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh

Bellevue PA

Neville Township PA

Neville Township PA

Baden PA

Rochester PA

Industry PA

East Liverpool OH

East Liverpool OH

East Liverpool OH

East Liverpool OH

Steubenville OH

Yorkville OH

Yorkville OH

Newport OH

Reedsville OH

Long Bottom OH

Portland OH

Antiquity OH

Racine OH

Middleport OH

Aberdeen OH

Maysville KY

Maysville KY

Maysville KY

Ripley OH

Ripley OH

Cincinnati OH

Cincinnati OH

Lawrenceburg IN

Vevay IN

Vevay IN

Cincinnati OH

Newport KY

Cincinnati OH

Bellevue KY

Dayton KY

California KY

Augusta KY

Augusta KY

Vanceburg KY

Worthington KY

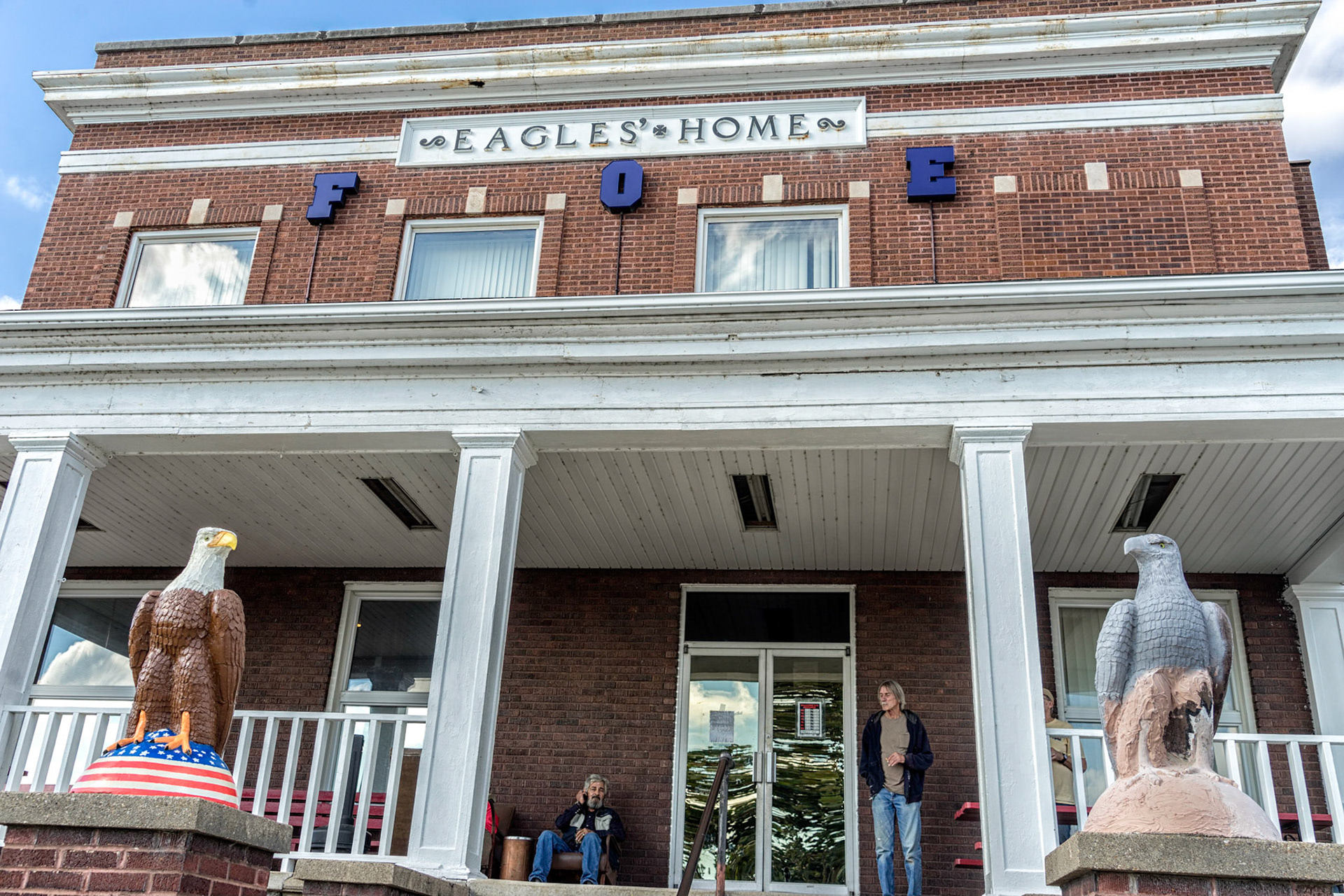

Huntington WV

Lesage WV

Point Pleasant WV

Point Pleasant WV

York WV

Ravenswood WV

Ravenswood WV

Moundsville WV

Benwood WV

Benwood WV

Wheeling WV

Wheeling WV

Wellsburg WV

Folansbee WV

Newell WV

Shippingport PA

Pittsburgh PA

Pittsburgh PA

Pittsburgh PA

Pittsburgh PA

Pittsburgh PA

Aurora IN

Aurora IN

Aurora IN

Rome IN

Tell City IN

Tell City IN

Tell City IN

Tell City IN

Troy City IN

Rockport IN

Rockport IN

Evansville IN

Evansville IN

Mt. Vernon IN

Old Shawneetown IL

Rosiclare IL

Bay City IL

Karnak IL

Metropolis IL

Metropolis IL

Metropolis IL

Metropolis IL

Metropolis IL

Joppa IL

Olmstead IL

Olmstead IL

Cairo IL

Cairo IL

Paducah KY

Paducah KY

Paducah KY

Paducah KY

Livingston County KY

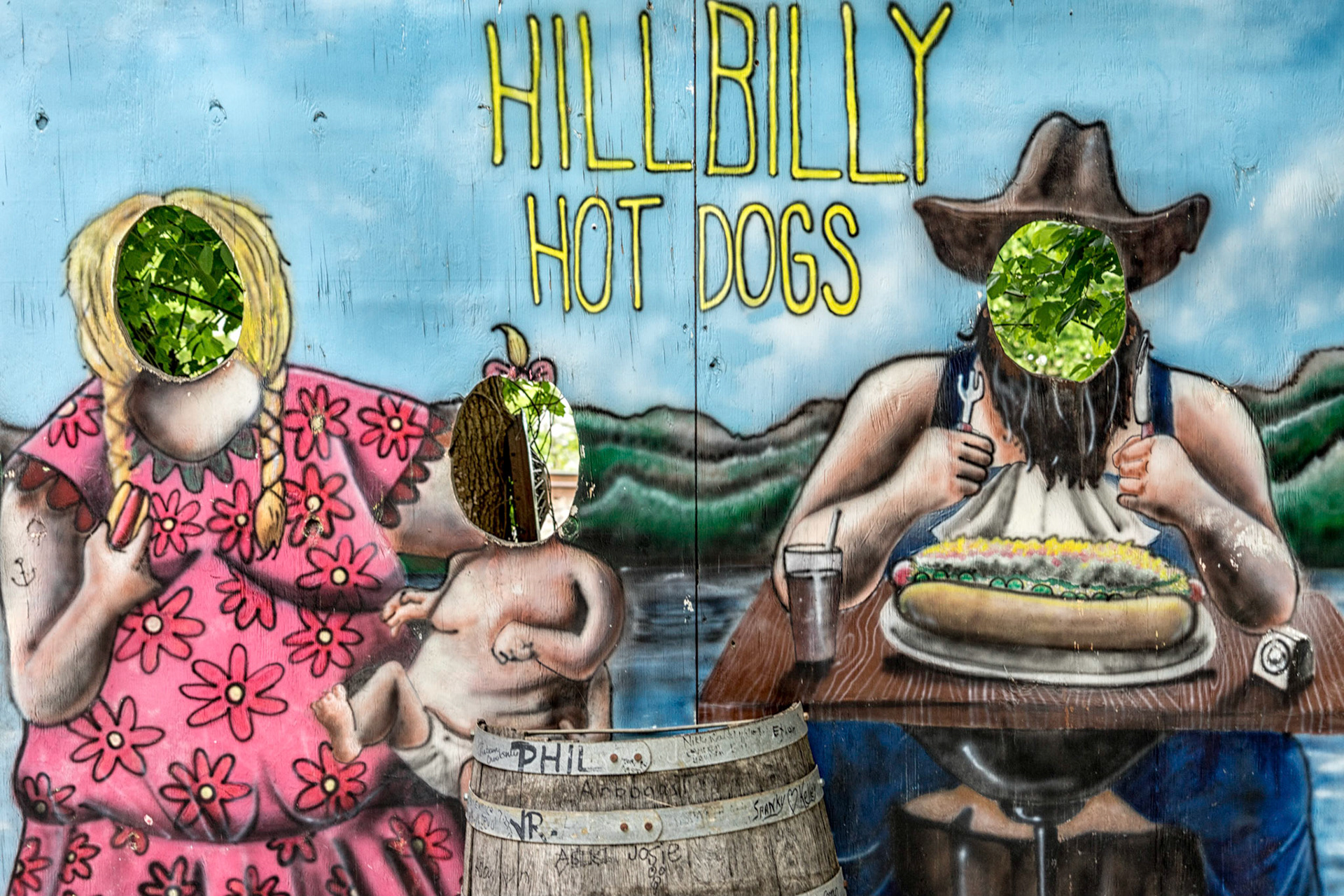

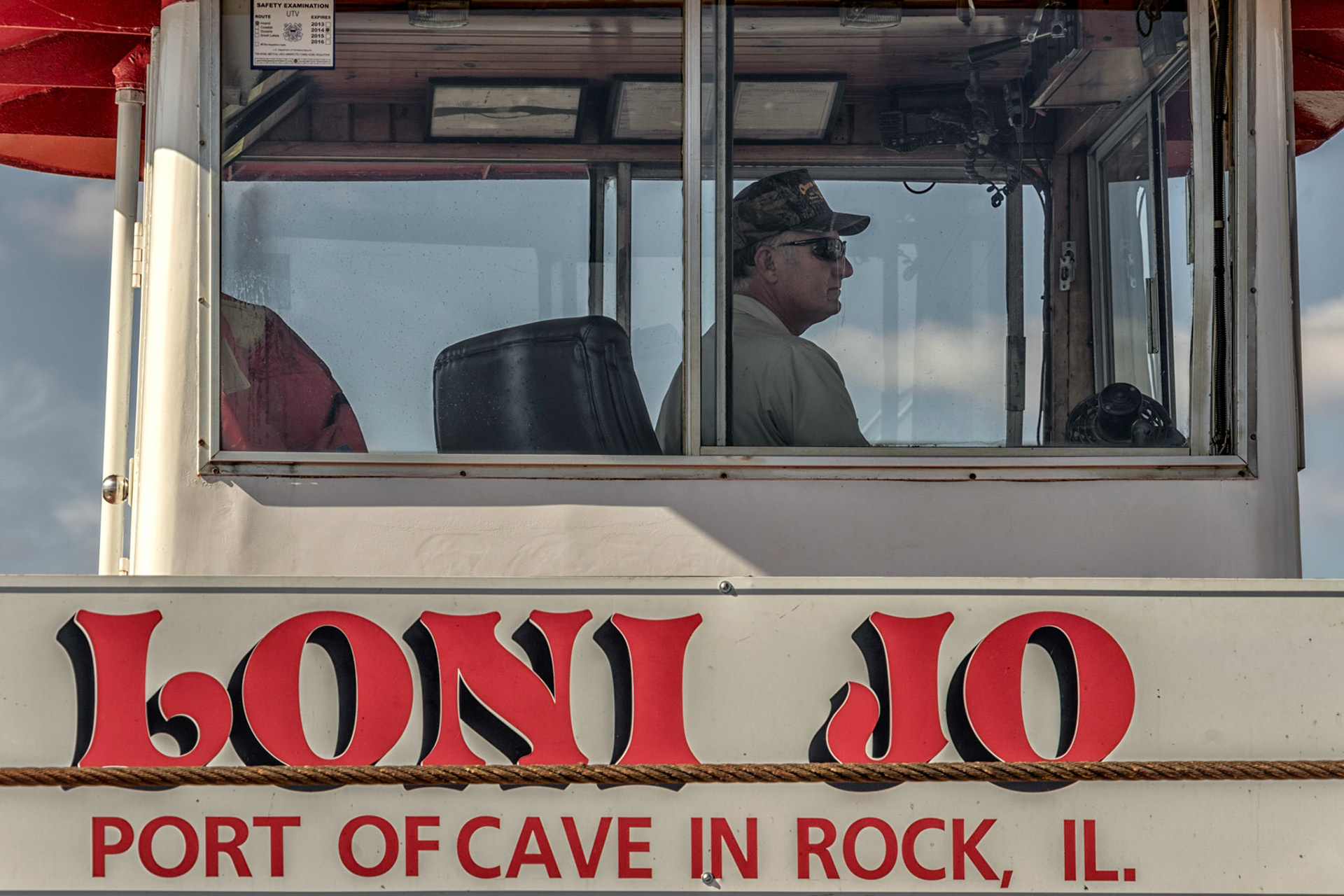

Cave-in_Rock IL

Cave-in_Rock IL

Crittendon County KY

Owensboro KY

Owensboro KY

Meade County KY

Louisville KY

Louisville KY

Louisville KY

Louisville KY

Louisville KY

Louisville KY

Louisville KY

Prestonville KY

Rabbit Hash KY

Belleview KY

Petersburg KY

Petersburg KY

Ludlow KY

Ludlow KY

Mason County KY

Higginsport OH